Indonesia, Literature, 2014

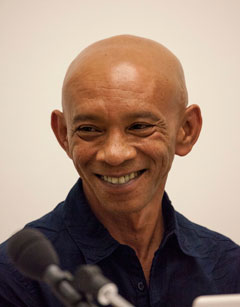

Afrizal

Malna

Within the differentiating canon of contemporary Indonesia’s literary scene, the writer Afrizal Malna, born 1957 in Jakarta and still residing there, embodies a highly unique voice. His poems – “physical encounters with urban space”, as the researcher and translator Andy Fuller, who teaches in Jakarta, describes them – establish a clear contrast not only with the pure intellectualism of, say, a Goenawan Mohamed, but also with the gentle romanticism Sapardi Djoko Damono represents. By comparison, Malna has doubts in language, and he elevates working on and with language to his strongest weapon in order to repeatedly put Indonesia’s long journey into modernism, accompanied by social and political rejections, to the test.

“Language is a monster that simultaneously creates and cancels communication”, writes Malna, who studied philosophy, demonstrating his puzzling sense of humor in the introduction of his volume of poetry, “Second Hand Language Store A and B” (2012): Why – as expressed here – do people invent language to speak with people? Language is certainly always a problem – and a problem seems to be human speech. For this reason, in all his poems, he reflects, no, explores the complicated relationship between language, bodies, and space. “Complicated” applies since language – which one allegedly owns yet must repeatedly “make” – not least of all determines the poetic self’s location in space.

In the process, the philosophically-grounded humor of his poems couples not only with a profound sensuality but also with deeper political thinking. Indeed, his understanding of language is rooted in political literature. Malna dedicated himself to this immediately after his house was ransacked by security forces in January of 1974, during the course of the student protests against Suharto’s “New Order” doctrine, which ended fatally. In the 1980s and 1990s, he was a member of Teater Sae, which, like so many groupings to evolve from the thriving Avant-garde scene at that time, resisted Suharto’s regime. It used art as a means to give the socially disenfranchised and the marginalized a voice and space of their own. In the 1990s, Malna was briefly affiliated with the activists’ group “Urban Poor Consortium”, which even today criticizes the lack of living space for the poorest of the poor.

Therefore, when Malna, also a theater critic and novelist, thinks about the body, he means something extremely tangible – even when his poems meanwhile verge on cloaking themselves in playfulness; one needs only to listen to the sound of their titles: The Anthropology of Coca-Cola Cans, The Active Activities of Ice Blocks, and Busy Burning Trash, The Red Typewriter. Malna invariably starts with an everyday object – then immediately confronts his readers with irritating interruptions of sentences and meanings, which make the so-called familiar appear strange and puzzling. For the poet Ulrike Draesner, who met with Malna in 2012 and translated several of his poems into German, his poetry – an “entity existing between prose and poetry” – works syntactically: sentence by sentence – or should one say: sentence against sentence? This is true because the sequence is not linear; instead, it appears as skittish as syntax itself. Disparate objects are grouped referentially. Other sentences remain unfinished and ambiguous. This is an appellative poetry to be interpreted as splintered and likewise unending, a poetry that looks directly at the fragmented present-day of contemporary Indonesia.

Incidentally, with a double meaning attached, Malna calls the Indonesian language a language without a native country: going home – pulang kampung – means, on the one hand, returning to a small village in a small town. But Suharto’s New Order doctrine – for the sake of shaping a united nation – also resulted in the destruction of land and the uprooting those who lived on it. According to Malna, the Indonesian language famously resists all forms of domestication, and this, too, is why he searches for an Indonesian language as much in the position to reflect the neglected history of his native country as the fact that this “united” Indonesia is a construction.

In this respect, his poems remain outraged statements against his country’s intolerable social and politic conditions. They denounce the widespread lack of work and perspective to the same degree as the rampant corruption and the government’s “dead-body politics”. Environmental destruction and daily violence matter to Malna: “People are being raped. The land is being raped. The earth is being raped.” (“Dead-body Politics Hushed-Up by Newspaper”, translation: Ulrike Draesner) To this end, Malna transformed his language into an extremely flexible body, one that puts up a fight against bureaucratization and despotism, against overshaping and uniformity, against dogmas and banning: “Young people know their bodies are unnumbered ice blocks. They melt in order to hump. They melt in order to scavenge a job. They melt in order to buy shoes. And they become ice blocks again. They become ice blocks in order to melt. They become ice blocks in order to enter the house. They become ice blocks in order to go to school. They freeze and melt like the water shoved into the freezer” (in: “The Active Activities of Ice Blocks, translated by Ulrike Draesner).

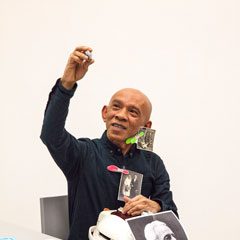

One can easily imagine what it’s like when he steps on stage as a performance artist: the wiry body filled with a unique presence; its voice a space-encompassing instrument instantly connecting the body with the audience. With Malna, whose productivity is enormous, everything is connected: his trips to international poetry festivals as an invited participant condense to essays and poems, and the poems lead to more trips. Practice and theory, experiencing and art, are inextricably one and the same thing.

In the introduction to “Second Hand Language Store A and B” (2012), he writes: “Water is only steady when it flows.” Using the same flexibility found in his poems, this poet forces, no, allows us to become as flexible as water – which we all know breaks stone.

Text: Claudia Kramatschek

Translation: Karl Edward Johson

Silke Behl / Ulrike Draesner: “Er steht da und beginnt zu sprechen”. Über Afrizal Malnas Gedichte. In: Sprache im technischen Zeitalter 204 / Dezember 2012, pp. 491-504

Past

-

druckmaschine drittmensch

Afrizal Malna2015, Book

Poetry. Indonesian and German. German by Ulrike Draesner. Interlinear translations by Katrin Bandel and Sophie Anggawi.