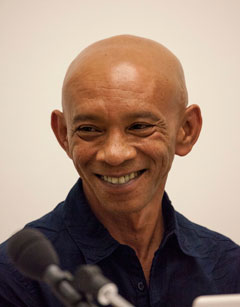

France / USA, Literature, 2015

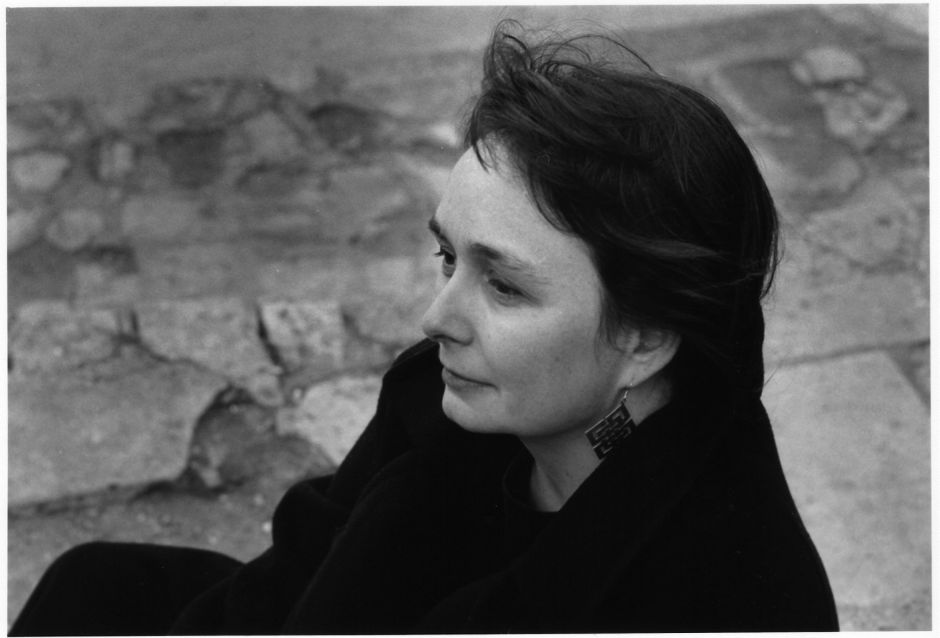

Ellen

Hinsey

An American ex-pat poet living in Paris, undertaking peregrinations across old Europe in search of the wounds of history – at first glance, this story sounds like a cliché. And yet it is impossible to use hackneyed images to capture the lyrical poet Ellen Hinsey, who was born in Boston in 1960. The same goes for her work, which she has carefully developed over the years. Hinsey first discovered literature as an autodidact: after earning a fine arts degree from Tufts University, she decided to move to the city on the Seine in 1987. The distance from her home helped breath new life into her language, allowing her to escape what she deems the “confessional idiom” of American lyric poetry (Ellen Hinsey in: The Philadelphia Inquirer, 5.28.1996).

Her own lyrical tone is a an astonishing mix blending a laconic American style with a striking economy of language and the melancholy of Eastern European literature, which she greatly admires and has translated in the past. Her use of language is exacting, measured, and brimming with precise constructions. Her images cannot be reduced to mere descriptions, but serve instead to really embody whatever she is describing. Her work includes references to Greek antiquity, and in her poems she employs a loose, elegant meter for couplets und quartettes, plays with rhymes and rhythms, alliteration, and highbrow allusions – and yet is a traditionalist poet at heart. Her debut publication was the 1996 volume Cities of Memory, which won the prestigious Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize. The unusual intellectual depth and earnestness of her voice was already evident in her first publication. The book’s title points to the volume’s themes of defeat and transition, of memory and disintegration, which the author conjures up by re-imaging key moments in European history: Spain in 1810; Sigmund Freud fleeing Vienna in 1938; and the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961. But she meditates on the sea of lights reflected in the Seine, too, which she sees as a metaphor for the volatility of life. In Hinsey’s view, lyrical poetry can be an ideal instrument to peer into the moral and philosophical nature of things – be it the individual, a landscape, or history. The latter passes by in Cities of Memory in a series of gloomy snapshots evincing contours of the real; for example, when a train enters a Berlin train station at night, right at the spot where the Cold War revealed its ugly nature with the Berlin Wall, Hinsey uses the image as a metaphor for the journey shared by the human race into the perennial uncertainty of the future. A depersonalized voice speaks in most of her poems, lending them an air of atemporality; at the same time, the author continually reminds us of the transience of life. Despite these themes, Hinsey’s work never seems didactic: in fact, the reader is seduced by the musicality and visual nature of her work, as well as by the evocative dialectic interplay between past and present, and by the roar of history in the echo chamber of the eternal. In Hinsey’s second poetry volume The White Fire of Time (2002), she considers the human pursuit of final, absolute knowledge. The three-part long-form poem – which is divided into shorter sections, sometimes aphoristic, sometimes essayistic, and with titles like “Commentary,” “Meditation,” and “Reading” – offers a bold – but ultimately successful – union of philosophy and theology. The reader finds traces ranging from the wisdom of the Upanishads to Simone Weil, and from the pre-Socratic philosophers to William Blake. Central to the author’s unique yet personal metaphysics is the Judeo-Christian Biblical tradition – and with it the question of the origin, power, and impotence of language. Her work evinces a seductive charm, like in her explorations “On Varieties of Flight,” and “On the Unique Cosmology of Passion.” She originally intended to call the volume “Vita contemplativa,” but a book with that kind of title would never sell in a country like America, which is for the most part unfamiliar with the European philosophical tradition. In her third volume of poetry Update on the Descent (2009), she nonetheless shows reverence not only to Dante’s Inferno, but also to the Platonic Dialogues: from the former she borrows the moral imperative of a vision of humanity that is clothed in inhumanity; and she takes the book’s dialogic structure from the latter, blending prose and aphorisms to create arrangements that are both playful and tightly composed. In these poems, Hinsey constructs nothing less than an anatomy of political violence: these poems contain excerpts of transcripts from the trial at the International War Crimes Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, which the author attended in February 2002. At one point she asks, “Why were the men separated from the women?” The question is enough to conjure up the horrors of a war marked by the unspeakable. The issue gets to the crux of each kind of literature: in this volume, she counters literature’s impotence in the face of the unspeakable with alternative, more inventive forms of speaking. In so doing, she makes the very philosophical and aesthetic dilemma inherent in creating literature out of second-hand testimony the subject of her work. For example, the first line of “Interdiction” reads, “It is said that we can no longer use the old words,” but then ends with, “But here, under the blackened sun, there are things, in the trammeled, the ruined, the old words, which must still be said.” Here, Hinsey does the impossible: not only does she translate this form of second-hand testimony into language, but she transforms it into the beauty of lyric poetry, thus capturing not just the horror of history, but also the hope for and belief in its renewal.

Text: Claudia Kramatschek

Translation: Amy Pradell

Camera/editing: Uli Aumüller, Sebastian Rausch

Sehen heißt ändern. Dreißig amerikanische Dichterinnen des 20. Jahrhunderts. Eine zweisprachige Anthologie. Published, translated, and with an afterword by Jürgen Brôcan. Edition Lyrik Kabinett. Munich 2006. pp. 130-141.

Imagination und Destruktion. Gedichte. In: Akzente, Heft 2/2009. Translated from English by Uta Gosmann and Maja Ueberle-Pfaff. Munich 2009. pp. 108-114.

Past

-

Des Menschen Element

Ellen Hinsey2017, Book (Spurensicherung Bd. 29)

Order: info@matthes-seitz-berlin.de