Turkey, Music, 2020

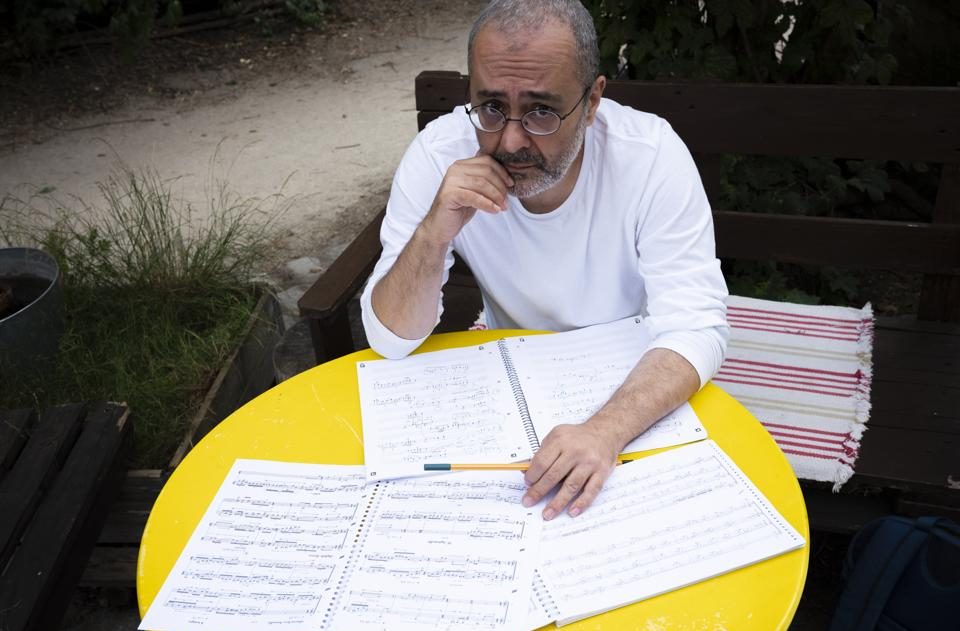

Emre

Dündar

Amid an undertone of wind instruments and solemn, fiery strings, of electronic hissing and noises, Emre Dündar’s voice resonates like an elongated plea. With fragments of sentences and words, sung and spoken sounds and vocalizations that switch suddenly from high to low registers, he gives voice to a sonic disappearance: his piece De Vulgari Eloquentia (2017) is dedicated to the last speaker of the Ubykh language from the Northwest Caucasus who died in Turkey in 1992.

“Each language has its own musical qualities,” says Dündar in conversation. “I improvised De Vulgari Eloquentia first, after that I made a spectral analysis of my voice. When you analyze a sound you understand there are so many secrets you can build upon. When I am writing phrases for instruments, I am creating connections between my speaking and my singing style.” Dündar’s scores, whether for orchestra, piano with electronics, or woodwinds in various constellations, are highly complex; he sees the use of symbols, typefaces, and playing instructions as his own art form. Entrusting contemporary musicians with his works, however, can present a challenge: “When musicians look at the scores, they first try to understand everything. But I want them to play a narrative phrase, or to speak as individuals.”

Poetry in particular appeals to Dündar. He composed a Soirée Gotique after poems by Emily Dickinson and devoted himself extensively to the sketches of modern Turkish poets İlhan Berk and Ece Ayhan. “Sketches are not closed but something still alive. Like a ghost, a paper to forget but this paper gives me the sound of the poetry. When I look at it I create an imaginary connection with the poet who tried his way through the mess of words. In poetry I constantly discover new structural formulas that I reconcile with musical narration.” Dündar is familiar with the oral traditions of his region, like those of the Aşıks minstrels who have been around for centuries in both Western and Central Asia. The Meddâhs were popular storytellers in Turkey who touched on current events and augmented their lectures with sarcasm and social criticism.

Dündar plays clarinet and alto saxophone, but his first instrument was the piano. He describes his mother, the concert pianist Meral Dündar, as a rigorous teacher. At the Istanbul Conservatory, he studied under İlhan Usmanbaş, the most important protagonist of modern contemporary music in Turkey. An exercise was to write pastiches of classical European composers. Officially, composers were supposed to integrate Turkish folk songs into classical music, much like socialist realism, Dündar says. Both skills serve him well when composing music for film; he appreciates being limited to addressing viewers directly and to production technologies he also uses for his electronic music. Once a month, he meets in the studio with fellow Istanbul Composers Collective members and records a variety of sounds anyone of them is welcome to use afterwards. And thus Dündar’s voice already resonates in the works of other contemporary Turkish composers.

Text: Franziska Buhre

Translation: Erik Smith